Abel Ferrara: My King of New York

Elliott celebrates April Ferrara with a dive into the filmmaker's singular career

Content warning: mentions of sexual assault in movies

Last year, Film Twitter personality Michael Mann Facts tweeted, "Abel Ferrara is like the Wario to Martin Scorsese’s Mario,” a silly joke that contains some nuggets of truth.

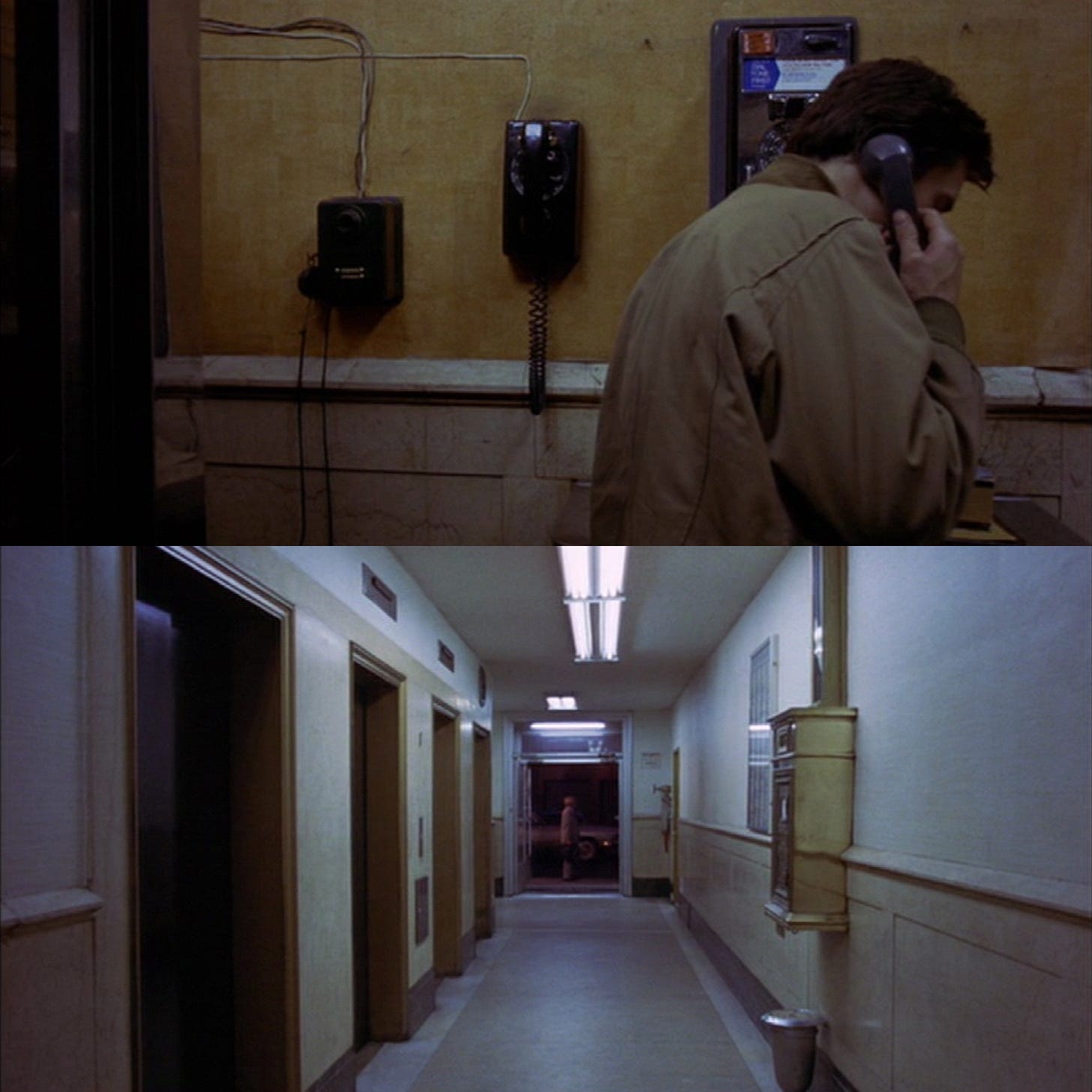

Taxi Driver was released in 1976, the same year as fellow New Yorker/Italian-American Abel Ferrara’s debut that’s titled, *ahem* Nine Lives of a Wet Pussy. If that sounds like the title of a porno, well, it’s because it is a porno. While Scorsese was making his iconic character study about Travis Bickle, Ferrara was making the movie that Travis would take Betsy (Cybill Shepherd) to in one of the cinema’s most infamous fumbled dates. When Travis humiliates himself further with a phone call to win Betsy back, Scorsese famously pans the camera to the hallway as the call unfolds, suggesting that Travis is too pathetic to keep in the frame, that the moment is too uncomfortable to witness. Marty uses the camera to do what our eyes would do if we were witnessing it in person, look the hell away.

In an Abel Ferrara film, the camera would move in closer to Travis. He made a career of making movies about characters at their lowest and most pathetic. We can basically feel the sweat and grub from his (typically male) spiraling protagonists. Let’s go through his wildly impressive career of post-Nine Lives of a Wet Pussy fictional works (haven’t seen any of his docs yet). Yes, I have seen Nine Lives and can use the excuse of research now that this piece exists. Not a ton to say about that one.

Ferrara wasted no time making a name for himself once his movies had his actual name attached to them (using the pseudonym Jimmy Boy L. for Nine Lives). He kicked off with The Driller Killer (1979) and Ms .45 (1981), both exploitation movies that became instant cult sensations. The Driller Killer is about an artist who turns insane from piling stress about deadlines, finances, a No Wave band playing in a nearby apartment, and the artist begins to kill homeless people with a power drill in blind spells of rage. The movie stars Ferrara himself in some meta casting — at the time a struggling artist, likely afraid about the idea of having to sleep outside if he can’t afford to do what he loves, and portraying a character that unleashes that fear on who he fears he could become. It’s a deeply disturbing (and hilarious depending on your sense of humor) flick, and despite all the blood and guts, nothing is more upsetting than the extended scene of Abel eating an entire pizza, and how he eats that pizza.

His sophomore effort, Ms .45, delivered on The Driller Killer’s promise right away. Coming out just a few years after Woody Allen’s Manhattan, a director and film that would romanticize the city, Abel paints a vastly different New York for us. Think of the opening of Lynch’s Blue Velvet, where the camera descends from the idyllic American neighborhood to the dirty, bug-infested underground. That underground is Abel’s New York; crawling with endless vermin (men) that prey on Thana (Zoë Lund), a mute seamstress who goes on a killing spree after being traumatized by multiple sexual assaults. It’s an extravagantly stylized pulp tale, filled with sicko humor and a cultural footprint that remains 40+ years later (I learned recently that a character from Euphoria sports Lund’s famous nun costume). Ferrara displays an uncanny understanding of editing and angles to alter the movie between upsetting and thrilling.

The rest of the ‘80s were all for-hire work that ranged from decent (1984’s Fear City) to completely forgettable (Gladiator and Cat Chaser). There’s one shining bright spot in the commercial era, 1987’s crackerjack China Girl, potentially his most underrated flick. A grittier, more violent play on the Romeo & Juliet/West Side Story narrative (the male lead’s name is literally Tony), China Girl showcases a director that’s in total control, balancing an ensemble of performers against a backdrop of eye-popping style in nocturnal sequences of gang rivalries and dancing lovers. It paints new colors of Ferrara’s New York City — one of brash violence in its diverse communities. More than any of the other legendary NYC filmmakers, nobody has better captured New York City as the city that never sleeps.

‘90s Ferrara is one of the greatest decades for a director in American cinema history (if you’re asking me) — 8 narrative films that range from great to masterpieces. No longer stuck making lower budget studio fare, he was able to make films on his own terms from his own scripts with actual stars. His ‘90s began with King of New York, the film that the burgeoning young filmmaker was building to. A loaded ensemble led by Christopher Walken as Frank White (a name later associated with Notorious B.I.G.) who gives one of my favorite performances ever as a Robin Hoodesque drug lord, vampiric with his pale skin and mourning eyes that look like they’ve witnessed hundreds of years of a broken system, and giving line deliveries (and strutting dance moves) that must be seen to be believed. People love doing a Walken impression, but nobody else could’ve given a performance like this.

Put in 5th grade terms, King of New York is cool as heck. Like his contemporary Brian De Palma, Ferrara demonstrates how style is substance. Shimmering neon blues glide across the city and there’s a dance/shootout sequence set to Schoolly D’s “Am I Black Enough For You?” that couldn’t be more blue, and couldn’t be more alluring. Quentin Tarantino can be all over the place with his film takes, but he’s spot on when he compares a phone booth killing sequence to a Sergio Leone set piece; there’s a grandness to this street murder through the rapid, jaunty edits of close-ups, overpowering sound, and seemingly boundless bullets and blood. Amongst all this style there’s a complicated morality at the film’s center; a movie that explores capitalism and socioeconomic inequality, police corruption, and how Laurence Fishburne and Christopher Walken are some of the coolest guys to grace the screen.

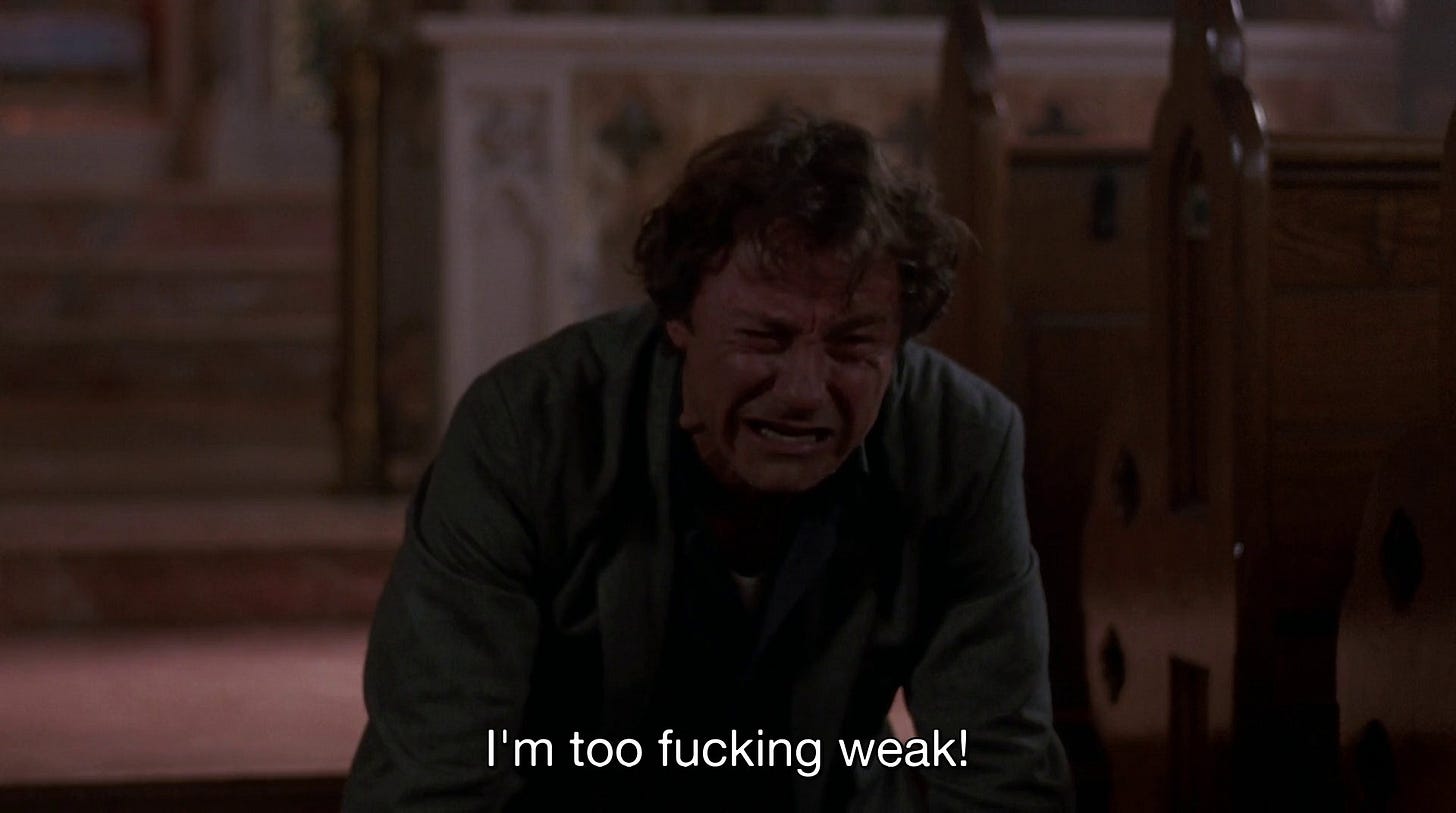

Martin Scorsese was the director known for crime films with immoral characters that can’t escape their catholic guilt. Ferrara was right there with him with 1992’s Bad Lieutenant, even casting Scorsese’s original muse Harvey Keitel to play the lead. Ferrara’s religious convictions and imagery go back to The Driller Killer (the film opens in a church) and Ms. 45 (Zoë Lund sports an iconic nun look in the film’s final set piece). To bring the Mario/Wario comparison up again, Scorsese’s character of Charlie (Keitel) the gangster in Mean Streets is a boy scout compared to the degenerate NYPD Lieutenant of Ferrara’s picture. When The Lieutenant (we’re never given an actual name) isn’t smoking heroin on the clock, openly harassing women, or gambling his family’s money away on the Dodgers in the NLCS, he’s being visited by an apparition of Jesus and wailing like a newborn as he pleads to be forgiven for his unending list of sins.

There’s a shift between King of New York and Bad Lieutenant. King is stylistically enticing. We love Walken’s Frank White and we’re drawn to him, but Keitel’s The Lieutenant is repellent. Frank White’s pain is concealed and mysterious. The Lieutenant’s pain is naked (literally). Bad Lieutenant is drier too; gone are the lush textures of King of New York, replaced by brown and limp (though always compelling) cinematography. It’s an unflinching film. Ferrara was just getting started making those

He teamed up with Keitel again the following year to make Dangerous Game, equally distressing as their previous collaboration and far less commercial (despite Bad Lieutenant having an NC-17 rating). It’s even more surprising how uncommercial it is when you look at Keitel’s co-star — 1993 height-of-her-fame Madonna (who is astonishing despite her later trashing the film). Keitel stars as film director Eddie Israel who is making an arthouse film about a spiraling marriage just as his own marriage is crumbling. Israel is a not so subtle stand-in for Abel himself, a director who’s so consumed with his work, so obsessed with artistic integrity, that down to earth reality becomes inaccessible, and it renders him to be, as Norm Macdonald says, “a real jerk.” For Ferrara heads (i.e. me), Dangerous Game is one of his best.

Two of Ferrara’s ‘90s joints were horror films. The first was Body Snatchers (1993), the third adaptation of Jack Finney’s 1955 novel after Don Siegel and Philip Kaufman both made classics. It’s the last major studio film he ever made and the weakest of a crazy prolific decade, though still a strong movie that he directs the hell out of, packed with his signature dread of bad things a-coming (and features an all timer horror performance by Meg Tilly).

The second horror film was 1995’s The Addiction, a vampire movie back in Ferrara’s independent roots. Shot in cold but beautiful black and white by the amazing cinematographer/12-time Ferrara collaborator Ken Kelsch, The Addiction approaches the vampire tale from the perspective of an addict. Lili Taylor’s Kathleen develops an unquenchable thirst for blood, with that comes the same kind of behavioral changes that you’d see from somebody at war with addiction. There are plenty of references to drugs too - Cypress Hill’s “I Want To Get High ”, William S. Boroughs’ Naked Lunch is mentioned. The Addiction’s nightmarish hip-hop needle drops and images that pair blinding white with cloaked dark shadows cast a beguiling spell. It’s one of his coolest movies, and one of his saddest.

The next year gave us The Funeral, a fairly straightforward crime affair. Bringing back Christopher Walken after a one-scene part in The Addiction (the superior one-scene Walken performance to Pulp Fiction if you’re asking me), it’s a gangster drama concerning three brothers in a crime family. The Funeral is boringly good — damn solid as a movie, anchored by another terrific Ferrara ensemble (s/o Annabella Sciorra), but he was making far more compelling films at this stage.

Like ‘97’s The Blackout, the harrowing movie where Abel again tackles addiction, but this time without the remove of genre/vampires. Nick Newman sums it up well when he says, “some movies really shouldn’t be seen with other people.” The film itself feels hazy and drunk, with too close for comfort Dutch angles of Matthew Modine’s numerous rock bottoms paired with absorbing dissolves as time and space bleed into one another, the film formally embodying the disorientation that comes when you’re constantly under the influence. I both admire and love The Blackout, it is brazen (in subject and filmmaking) and you can feel it searching for notes of grace. Ferrara couldn’t find those notes just yet. The film is more powerful for it.

The final ‘90s Ferrara also feels like the final film of its decade, nay, its millennium — as it anticipates a bleak and transactional new world of the 2000s. New Rose Hotel (1998) is one of my favorite films of all time and what I believe to be his opus. Why? Stay tuned for when Shawn and I get to it in a couple weeks :)

Following 9/11, Ferrara moved to Rome where it would be easier to finance his independent films. Just before that venture he released ‘R Xmas, a thriller starring TV legends from The Sopranos (Drea de Matteo and Lillo Brancato Jr.) and Law & Order: SVU’s (Ice-T). It’s a modest, tight flick with outstanding turns from de Matteo and Ice-T. There aren’t many movies I’d consider minor Abel, but this is one of them.

2005’s Mary and 2007’s Go Go Tales both feel spiritually connected to Bad Lieutenant; the former for its anxiety/crisis of faith, the latter for its degenerate, breathing-down-your-neck stress (Uncut Gems owes a lot to both Lieutenant and Go Go Tales.) Mary is one of his most sneaky moving and existential works, and Go Go Tales has probably his funniest ending (in a career full of those!) I love both films dearly.

Willem Dafoe previously collaborated with Ferrara on New Rose Hotel and Go Go Tales, but it was 4:44: Last Day on Earth (2011) where he established himself as Ferrara’s permanent muse/stand-in. It’s also when Ferrara’s films slowed the hell down. His sober period, you could say (he’s been sober for 12 years now). 4:44: Last Day on Earth depicts the end of the world and how a married couple live out their remaining hours together. It’s the first Dafoe pairing that deals with sobriety, the other comes a decade later in Tommaso (2019). Dafoe plays a filmmaker in both, while Ferrara’s girlfriend at the time plays the wife in 4:44, and his present day wife plays the wife in Tommaso, shrinking the gap between muse and director. Tommaso is the better movie, but both find the grace notes he was searching for in The Blackout and Bad Lieutenant, even if jealously, insecurity, and, unrest continue to plague the director/protagonist. There are glimpses of peace. But they don’t last too long.

Dafoe and Ferrara made two other films together. The first is 2014’s Pasolini, a radical biopic of one of his heroes and influences, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Italian filmmaker/poet/writer/and more most famous for the film Salo: Or the 120 Days of Sodom. It’s unlike any biopic I’ve seen in that it lives and breathes Pasolini’s vision and voice rather than simply showing events of his life. It isn’t all successful, but it’s another affecting exercise in Ferrara’s investigation of the tortured soul of the artist.

Then there’s 2021’s Siberia, one of his weakest. It’s a movie that’s so in my bag on paper (I heard it described as Ferrara going Tarkovsky mode) — but the results fall short and the film’s uncharacteristically elementary in its psychology despite some stunning visuals. I’ll go ahead and mention Padre Pio (2023), his most recent movie starring Shia LaBeouf that I think actively sucks, attempting to do two movies at once and one of them feeling totally inept.

The two late-career masterworks that I rank highly are 2014’s Welcome to New York and 2021’s Zeros and Ones. Zeros and Ones honestly begs for another watch before I make the claim that it’s top 10 Abel (I was very much Homer Simpson watching Twin Peaks when I watched it), but the images (working with one of the best working cinematographers Sean Price Williams) and ideas are so enrapturing that I cast my mind to the sidelines, went along for the visceral ride, and left feeling serene/that I also maybe watched the definitive Covid-19 movie?? It’s also the only other Ferrara that feels deeply connected to New Rose Hotel. Damn high praise from me.

Then there’s his greatest late period film, Welcome to New York. Horrible people in Ferrara films…there’s no shortage of them. Yet none are more repulsive than Devereaux (played by Gérard Depardieu, by many accounts a monstrous person himself) in Welcome to New York, based on the true story of a prominent French politician who sexually assaulted a hotel maid. Devereaux is a snarling boar of a man with loads of power and zero consideration for his fellow person.

I love Paul Schrader and I’m with everybody when they talk about him being one of the only American auteurs making (actually good) movies about the present moment…but let's also put some respect on Abel Ferrara's name in that department. Few films demonstrate such a bleak understanding of the corruption and injustice of our contemporary world. Its unhurried pacing and show, don’t tell (or sway opinion) approach delivers a gut punch that’s hard to shake days after viewing.

*deep breath*

Now, who’s excited to marathon all of these super feel good films I’ve written about?? Happy April Ferrara everybody! If you’re a novice, check out King of New York. It’s a perfect entry point and loose and fun (and yes still violent as hell).

Closing thoughts? I’ll borrow what one of my favorite working film critics K. Austin Collins’ said about the man in his Letterboxd entry for Dangerous Game: “Abel is my Godard.” He’s mine too. A boundary pushing filmmaker who makes me feel 50 disparate things in the span of a few minutes when I watch his movies. That applies for films he made three years ago, and for films he made 43 years ago. I love cinema and all its possibilities so much that I want to be challenged by it. Ferrara does that for me. And at cinema’s best, I want the way I see the world to shift. Ferrara does that for me too.

If that all sounds like homework? Trust me. . . not many directors make scenes as fun and joyous and thrilling as Abel Ferrara (watch the King of New York clip in the middle of this piece to see what I mean). He’s the full package.

He’s my King of New York.

Yes, definitely ready to marathon Ferrara! So many I've missed along the way, but god do I love Bad Lieutenant and King Of New York.